The objective of the 1985 Vienna Convention is to preserve human health, and to protect the environment from any harmful effects of the depletion of the ozone layer. The objective of the 1987 Montreal Protocol is to repair the ozone layer through the worldwide control, reduction and ultimately elimination of production and consumption of ozone depleting substances. The latest extension of the Montreal Protocol in 2016 – the Kigali Amendment – regulates hydrofluorocarbons as well. These chemicals are currently in use as a substitute for ozone-depleting substances, but are themselves potent greenhouse gases.

1. The international treaties on the protection of the ozone layer

After the mechanism by which chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) destroy ozone was proved in the 1970s, and the depletion of the ozone layer was observed in the 1980s, two international treaties to protect the ozone layer were signed under the aegis of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): the Vienna Convention (1985) and the Montreal Protocol (1987). These treaties have since been ratified by all Member States of the United Nations.

The objective of the Vienna Convention is to preserve human health, and to protect the environment from any harmful effects of the depletion of the ozone layer. The Convention encourages research activities, cooperation and the exchange of information between states, and national legislative measures, without however prescribing any concrete measures. In Switzerland, the Vienna Convention has been in force since 22 September 1988.

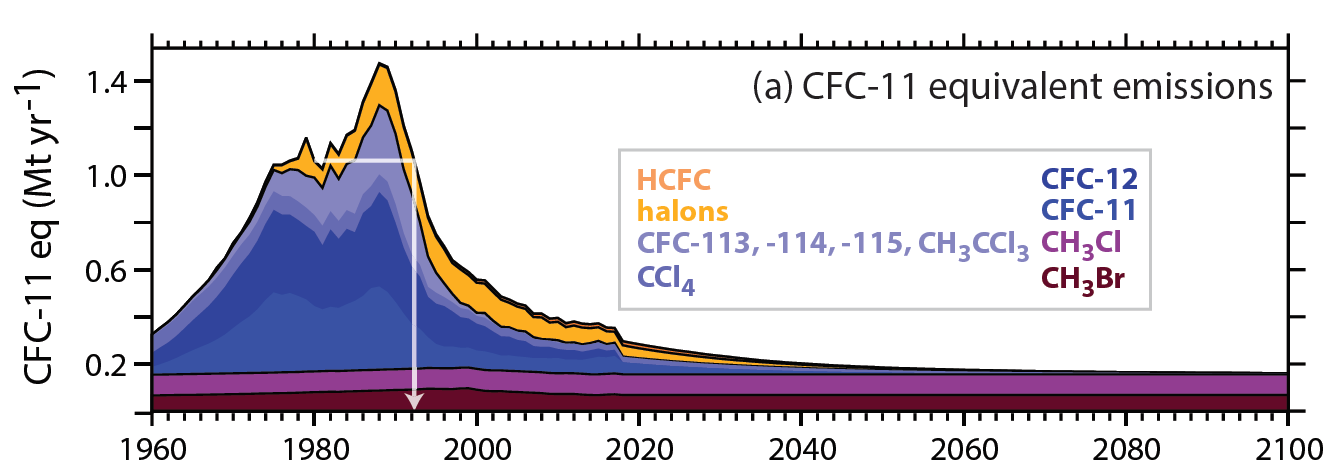

The objective of the Montreal Protocol of 1987 is to repair the ozone layer through worldwide reduction and ultimately elimination of ozone depleting substances. Its implementation has enabled the production and consumption of these substances to be reduced by more than 98% between 1986 and 2016. As a result, atmospheric emissions have also decreased sharply (see chart below), and the hole in the ozone layer over the Antarctic seems to have reached its maximum. However, we will still have to wait at least till the middle of the 21st century before the ozone layer returns to its pre-1980 state, as ozone depleting substances continue to leak from existing objects, products and wastes, and these substances have a long life-time.

Historic emissions of CFC-11 equivalents, derived from atmospheric measurements and model-based future projections. Image: WMO (2018) Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2018, Figure ES-1. Report available at www.ozone.unep.org > science > SAP

Since many of the substitute chemicals (HFCs) are potent greenhouse gases with an effect more than a thousand times stronger than CO2 and thus contribute to global warming, the Parties to the Montreal Protocol resolved in October 2016 in Kigali (Rwanda), to extend the Montreal Protocol to HFCs (Kigali Amendment), and to reduce the production and consumption of these chemicals by 85% in the medium term. These provisions have been in force since 1 January 2019.

The Montreal Protocol provides a schedule for the reduction of the substances that it regulates. Deadline extensions have been granted to developing countries, and a multilateral Ozone Fond gives them the financial and technical assistance necessary to implement the Protocol.

- Adoption of the Protocol: 1987, and of its amendments: London: 1990; Copenhagen: 1992; Montreal: 1997; Beijing: 1999; Kigali, 2016

- Ratification by Switzerland of the Protocol: 1988 and of its amendments: London: 1992; Copenhagen: 1996; Montreal and Beijing: 2002; Kigali: 2019

- Worldwide ratification (Montreal Protocol and its first four amendments): 2014

Substances regulated |

Industrialised countries |

Developing countries |

|---|---|---|

| Elimination of production and consumption | ||

CFCs, carbon tetrachloride |

1996 |

2010 |

Halons |

1994 |

2010 |

Trichloroethane |

1996 |

2015 |

Methyl bromide |

2005 |

2015 |

HCFC |

2030 |

2040 |

Bromochloromethane |

2002 |

2002 |

| Reduction of production and consumption (% of initial volume) | ||

HFC |

2036 (15%) | 2045 (20%) 2047 (15%)* |

2. The multilateral Fund for the implementation of the Montreal Protocol (Ozone Fund)

The Ozone Fund (Multilateral Fund for the Implementation of the Montreal Protocol) was established in 1990, in London, at the second Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol. The principal aim of the Fund is to support developing countries in their efforts to phase out the use of ozone depleting substances – and from 2019 also HFCs – within the deadlines that have been set.

The Fund finances a variety of projects in developing counties and implements them with the support of the World Bank, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation (UNIDO), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Switzerland regards the Ozone Fund as an important means of rapidly achieving the Protocol’s objectives in developing countries. Switzerland considers it very important that the projects supported are not only favourable for the ozone layer, but also favourable for the environment in general.

Switzerland currently contributes about US$ 2 million to the Fund annually (total budget US$ 150 million per year). In 1997/1998, 2010/2011 and 2020/2021 Switzerland was a member of the Fund's Executive Committee, the task of which is to develop guidelines and supervise the activities of the Fund.

Switzerland also supports the implementation of the Montreal Protocol in developing countries directly. For example, Switzerland has been involved in bilateral projects on refrigeration technology in India, Indonesia, Argentina, Chile and Costa Rica.

3. Implementation of the Montreal Protocol in Switzerland

Since it was signed, the Montreal Protocol has generally been implemented successfully. The industries and trades concerned have developed alternative solutions for ozone depleting substances and most industrialised countries, including Switzerland, have largely been able to respect the commitments agreed.

In Switzerland, adherence to the international commitments is ensured through the provisions of the Chemical Risk Reduction Ordinance (ORRChem). Annex 1.4 of this ordinance regulates the manufacture, placing on the market and use of ozone depleting substances, while hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) are dealt with in Annex 1.5 (substances stable in the atmosphere), in line with the Kigali Amendment.

HFCs in particular may only be used where no substitute is available according to the state of the art. The falling line in the chart illustrates the targeted step-by-step reduction in HFC consumption.

HFC consumption can be reduced with the help of a number of alternative technologies, including the use of natural substances (hydrocarbons, ammonia or water) or synthetic products (e.g. hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs)). However, the breakdown product of HFOs, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), shows a phytotoxic effect and lasts for an extremely long time in surface waters and therefore presents a new environmental risk. From Switzerland’s point of view, therefore, we should concentrate much more on developing technologies that use natural alternatives.

In Switzerland, the success of such legislative measures and technological developments is monitored in part through atmospheric measurements. For instance, the Jungfraujoch station constantly measures levels of halogenated organic substances that damage the ozone layer and/or act as greenhouse gases and contribute to climate change. The measurements from this station are summarised in a dossier and are also available in a report. Moreover, the Jungfraujoch station is part of the global AGAGE network, which has a total of 13 monitoring stations.

Last modification 04.12.2024