Climate change is exacerbating the threat of natural hazards. In the Saas Valley in Valais, experience clearly shows the importance of monitoring hazardous processes for the safety of people, towns, villages and transport routes. A forward-looking land-use plan is also important – not just in Valais, but everywhere.

Text: Lukas Denzler

The landscape of the Saas Valley and its communes of Eisten, Saas-Balen, Saas-Grund, Saas-Fee and Saas-Almagell is dominated by steep mountainsides. The locals have lived with natural hazards for generations. They try to protect themselves, but climate change is exacerbating the risk to towns and villages, roads and tourist facilities. Back in 2010, the communes of the Saas Valley carried out a case study on adapting to climate change – with a focus on natural hazards. Glacier retreat is the most striking change in this area; changes to the soil and rocks are less obvious but are key factors in erosion, rockfalls and rock avalanches.

Dangerous temperature changes

Norbert Carlen works for the Canton of Valais as a natural hazards engineer, with responsibility for the Saas Valley. He says that dramatic temperature changes, with hot and cold periods occurring within a short period of time, are becoming more frequent. “The freezing and thawing processes increase the risk of rockfalls and rock avalanches”, he explains. Moreover, as the glaciers retreat, they leave behind areas of loose material. In combination with heavy rainfall or sudden flows of water from the glaciers, this can lead to unpredictable debris flows.

As head of the regional security service in the Saas Valley, Urs Andenmatten keeps a close eye on weather patterns. The Joint Information Platform for Natural Hazards (GIN) operated by the federal government is very helpful for assessing risks. Natural hazard experts in the cantons and communes can consult the GIN platform for current measurement and monitoring data, forecasts and warnings. According to Andenmatten, rockfalls primarily occur in the spring after the snow melts, but can also occur in summer and autumn after heavy rain. “These days, when we have to close the cantonal road, it is more often because of rockfalls than because of the risk of avalanches”, he says. In response to the changing situation, 3,800 metres of rockfall nets have been installed in recent years.

Warnings of glacial ice avalanches

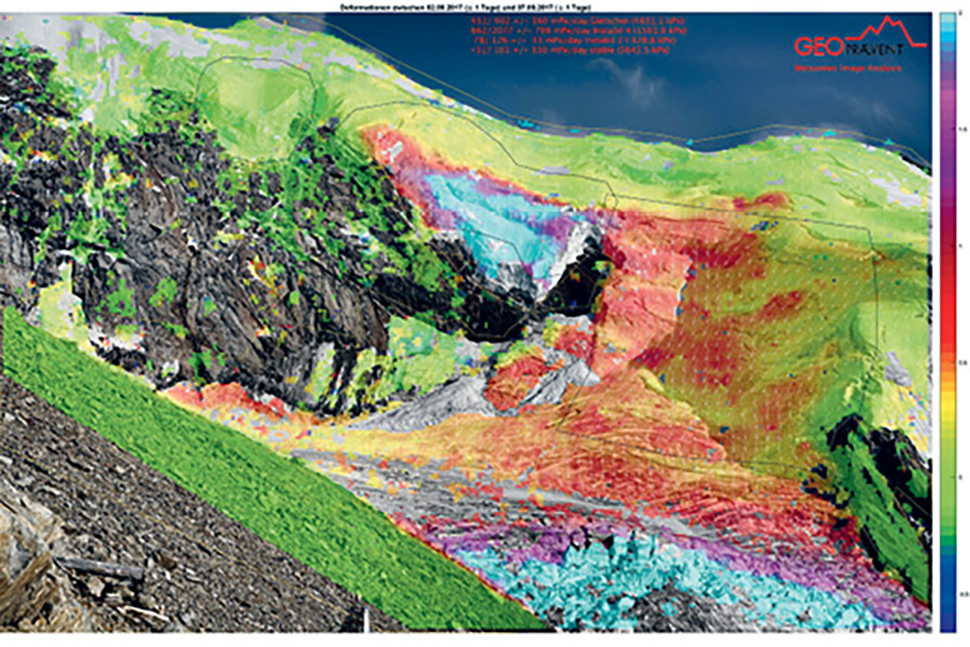

The Trift glacier above Saas-Grund has attracted lots of attention in recent years. In summer 2014, there were increasing incidents of ice breaking off the glacier. Since there was a risk of more ice breaking off, a monitoring system was set up in October 2014 with radar equipment, GPS points and a camera. When the situation calmed down again, a much cheaper monitoring camera was installed; this provides high-resolution images each hour when visibility is good. In September 2017, the cracks became wider and communal and cantonal officials decided to resume radar monitoring immediately.

The measurements indicated that ice would soon break off again, so the crisis team evacuated over 200 people. Only a few hours later, early one Sunday morning, the dreaded glacier collapse occurred, but without causing any real damage (see graphic above). The cost of radar monitoring is generally between 300 and 500 Swiss francs per day. In the case of the Trift glacier, the canton covered around half of the costs, and the mountain transport companies also contributed. “The commune had to pay around 35 percent of the monitoring costs”, says Saas-Grund mayor Bruno Ruppen.

In the meantime, glacier activity has calmed down again, but the cameras are still running. In summer 2019 there were two more minor incidents of ice breaking off. Based on an analysis of the images, officials had closed the hiking trail to Saas-Almagell for half a day as a precaution. The communes are responsible for maintaining some 300 kilometres of hiking trails in the Saas Valley.

Path closures because of rockfalls are quite frequent. Safety boss Urs Andenmatten makes an initial assessment when an event occurs. In the case of a major event, an assessment is carried out by a geologist from the canton. Two years ago, for instance, the hiking trail from Grächen to Saas-Fee was closed for a few weeks after the snow melt. It is important, Andenmatten explains, to put up clear information at the starting points of trails so that hikers do not suddenly find themselves in front of a barrier with no option but to turn back (see box).

The Gruben glacier on the Fletschhorn and the lakes in the glacier forefield above Saas-Balen also pose a risk. Urs Andenmatten checks the lake outlets every spring and autumn. The outlet of the lake by the glacier itself was dredged a few years ago to prevent the lake expanding too much. There is also a risk that heavy rainfall could dislodge debris in the glacier forefield and cause a debris flow that could reach Saas-Balen. Discussions are currently ongoing to decide how to reduce the risk along the Fellbach river.

Automatic remote monitoring

There are around 80 potentially hazardous glaciers in Valais. Three of them – the Trift glacier and the Weisshorn and Bis glaciers in the Matter Valley – are being closely monitored. Glacier monitoring is integrated in the canton-wide monitoring system for natural hazards. Experts in private engineering companies monitor and interpret the transmitted data on an ongoing basis. The cantonal office for forests, river works and landscape runs an automated remote monitoring system comprising hydrological and meteorological measuring stations, cameras and radar equipment, as well as sensors installed on site to record rock and earth movements.

According to Hugo Raetzo of the FOEN’s Hazard Prevention Division, the way the Canton of Valais uses and harnesses its monitoring systems is “pioneering work”. The canton is also involved in the pilot project on adapting to climate change. At the moment, experts are looking at the consequences of warmer temperatures for the permafrost, and with hazards arising from thawing rock faces. Unlike protective structures and protection forests, measuring and monitoring instruments cannot prevent damage. But they can save lives when used in combination with organisational measures, such as evacuation and closures. As Hugo Raetzo explains, “With hazards like glacial ice avalanches and rock avalanches, which simply cannot be prevented by technical means, often the only options left to minimise damage are monitoring and warning systems.”

Moving out of hazard zones

In the medium term, however, it makes sense to avoid using hazard zones, where possible. “A systematic decoupling of use restrictions and hazardous areas is an option that is often not explored seriously enough”, says Reto Baumann of the FOEN’s Hazard Prevention Division. And it is not just a matter of considering the next few years – protective structures and technical systems have to be maintained on an ongoing basis. That costs money, and maintaining them could become a burden for future generations. Decoupling usage from hazard zones is therefore sometimes the most sustainable solution. The FOEN’s brochure entitled Raumnutzung und Naturgefahren (Land-use and natural hazards), published in 2017, provides examples of where and how this strategy has been successful.

For example, in Weggis (LU), five properties have been successfully removed because of a serious risk of rockfalls. In Guttannen (BE) too, a property and a barn have been taken down because of the risk of debris flows. In Preonzo (TI), the canton relocated several industrial and business operations that were directly below an unstable mountainside. And in Nax and Sitten in Valais, several buildings that were located in a high risk zone have been dismantled and moved.

Ten years ago, the communes in the Saas Valley turned their gaze to the future with their case study on adapting to climate change. In view of advancing impacts of climate change, the challenge is to keep finding the right balance between protecting against and avoiding natural hazards. “When assessing hazard zones, we always take into account new conditions, some of which are the result of climate change”, says natural hazards engineer Norbert Carlen. If new red zones have to be defined on the hazard map and if they include as yet undeveloped land in the building zone, that land will have to be dezoned.

Better monitoring with satellite images

Radar satellite monitoring offers new possibilities for monitoring mass movement processes. The FOEN is able to use images from the Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), which are produced by the Sentinel satellites of the European Space Agency (ESA). With this data it is possible to carry out wide-area assessments that can also reveal slow or incipient slope movements.

The FOEN tested the capabilities of satellite monitoring in pilot projects in the area around the Aletsch glacier and in the Saas Valley. Now, thanks to a motion passed by the National Council and the Council of States, and to the Federal Council Decree of June 2019, the financial resources needed to cover the running costs and further development of natural hazard warning systems are also secure. This means in particular that it will be possible to close gaps in the monitoring of mass movement processes.

Climate change and hiking trails

Many mountain and Alpine hiking trails run just under the permafrost zone and will be exposed to more rockfall processes or debris flows in future. The Federal Act on Footpaths and Hiking Trails stipulates that the cantons must take care of path upkeep, signage and safety. The responsible authorities therefore also have a duty of care and information. However, certain hazards, such as unexpected rockfalls, cannot be ruled out. As a basic principle, hikers bear a high level of personal responsibility, which increases with the difficulty of the trail.

The pilot programme on adapting to climate change, led by the FOEN, is currently investigating the impacts of future natural hazards on hiking trails, their planning, construction and maintenance, as well as on organisation and processes. The aim of the Safe Hiking 2040 project is to supply those responsible with technical principles and operational frameworks so that they can continue to ensure maximum levels of safety in the future.

Further information

Last modification 03.06.2020